The Great Cattle Trail

A Commemoration of the Trail Drive Era

The Great Cattle Trail is a commemoration of cattle drives which depicts a cattle drive beginning in south Texas, continuing through Indian Territory/Oklahoma and ending at a railhead in Kansas. The trip took around three months, the cowboys were paid about a dollar a day, and many hazards were encountered. After the end of the Civil War cattle were abundant in Texas and a means was needed to get them to market in the East. Joseph McCoy built stockyards along the Kansas and Pacific Railroad, and the cattle drives began.

In the introduction to the Trail Drivers of Texas, B. Byron Price wrote that an “estimated 25,000 to 30,000 men trailed six to ten million head of cattle and a million horses northward from Texas to Kansas and other distant markets…” Price estimated that the typical cowboy took to the trail between age 16 and 22, 20% were older and 5% younger. About 60% went more than once. ’Cowboys,…are romantics, extreme romantics, and ninety-nine out of a hundred of them are sentimental to the core (Larry McMurtry). The stories from these men, and women, form the core of The Great Cattle Trail.

The individual pieces are based on the major books written about the trail, diaries, and memoirs published by cowboys. The work was based on six months of research in Oklahoma archives and libraries and drew heavily upon the 1920 publication "The Trail Drivers of Texas", which contains about 150 first-hand accounts of occurrences on the trails. These accounts formed the basis of many of the individual pieces in the exhibit. I included text from these sources as descriptions of the pieces, so that the focus of the work balances the experiences of the trail drivers with the general history of the cattle drives.

I also spent time at the National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum (NCWHM) archives, the University of Central Oklahoma Archives (thanks to Diane Rice and Jean Longo), the Oklahoma History Center, and the Oklahoma City Metropolitan Library. Special thanks to the library and archives staff at the NCWHM – Karen Spillman, Kera Newby, and Samantha Schafer.

The work was supported by a special-projects grant from the Oklahoma Visual Arts Coalition.

The Great Cattle Trail, a Commemoration of the Chisholm Trail

34” x 36”, Acrylic on tooled leather

The skull floating in the air reflects the logo on the Kansas and Pacific Railway map (see “The Best and Shortest Route”) to the railheads in Kansas, and paintings by Georgia O’Keeffe, as well as the state bird of Oklahoma, the Scissortail Flycatcher. This and the other tooled leather pieces commemorate the trail drive era and present a small representation of life on the cattle drives.

A Cactus of Texas

23” x 7”, Acrylic on tooled leather

“San Antonio was a gathering place for herds trailed in from ranges in the west and southwest. While the herds grazed at the edge of town, cooks could replenish their supplies and drovers could find diversion in the many saloons and gambling halls.” (Wayne Gard, The Chisholm Trail).

Many of the trail drives started in April, when Earth was greening up from winter and the spring flowers were beginning to bloom. Several of the drovers commented in their reminiscences how beautiful the land looked as they started out. Three pieces in the Long Hard Ride represent natural beauty, A Cactus of Texas, The Acanthus Rose, and A Sunflower of Kansas.

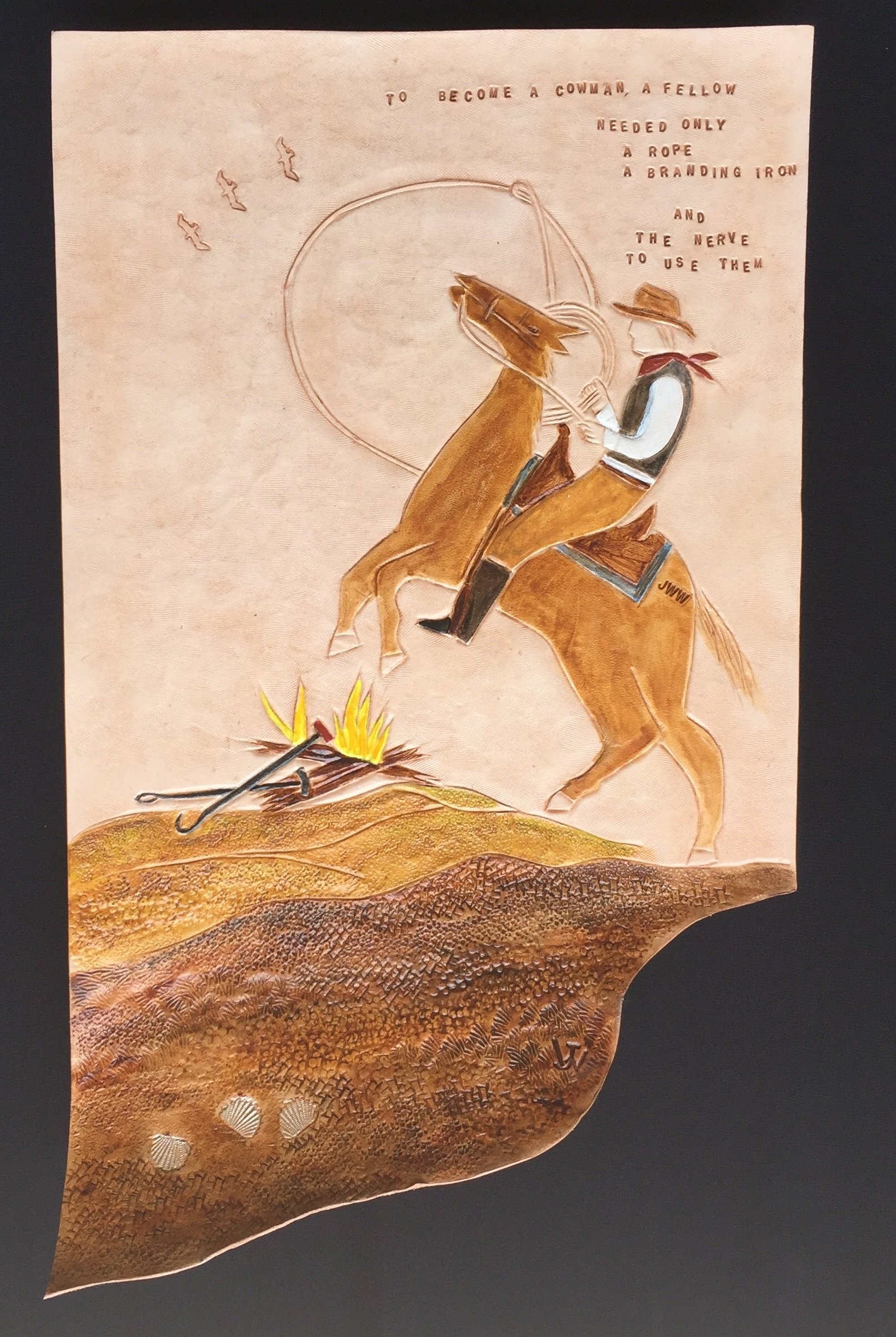

To Become a Cowman

17” x 10”, Acrylic on tooled leather

“ … to become cowman, a fellow needed only a rope, a branding iron, and the nerve to use them.” (Wayne Gard, The Chisholm Trail).

And probably at least a horse.

The Country is Alive with Stock

10” x 31” Acrylic on tooled leather

At the end of the Civil War, Texas was filled with loose stock, and the cattle trails and rail facilities in Kansas provided the means to get the cattle to market.

“As far as the eye can reach in every direction, and as far as you may go, the country is alive with stock. The whole market of the United States might be supplied here, and there would not be any apparent decrease.” Howard Union Newspaper, October 12, 1865 (James Sherow, The Chisholm Trail: Joseph McCoy’s Great Gamble).

“Scarcely a day but a drove passes. A stranger would imagine that beef, milk, and butter would be scarce and high; but the number is not missed, and the market is not in the least affected (Wayne Gard, The Chisholm Trail).

33 Flying M XS

20’ x 7 ¼”, Dyed, branding iron, tooled leather

Brand marks found on some of the hides used for The Great Cattle Trail.

The Best and Shortest Cattle Trail

24 ½ “ x 26”, Dyed, branded, tooled leather. Paper.

The Kansas and Pacific Railway distributed free maps and booklets showing the route to their stockyards in Kansas. The map probably “helped” the drovers to bypass the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railway facilities that would be encountered first.

“Guide Map of the Best and Shortest Cattle Trail to the Kansas Pacific Railway, with a concise and accurate description of the route: showing distances, streams, crossings, camping grounds, wood and water, supply stores, etc. From the Red River Crossing to Ellis, Russell, Ellsworth, Brookville, Salina, Solomon, and Abilene.”

The Coyotes’ Dream

29 ½” x 18”, Dyed, branded, tooled leather

The wail of the wolf and the coyote accompanied the cattle and might be the cause of a stampede.

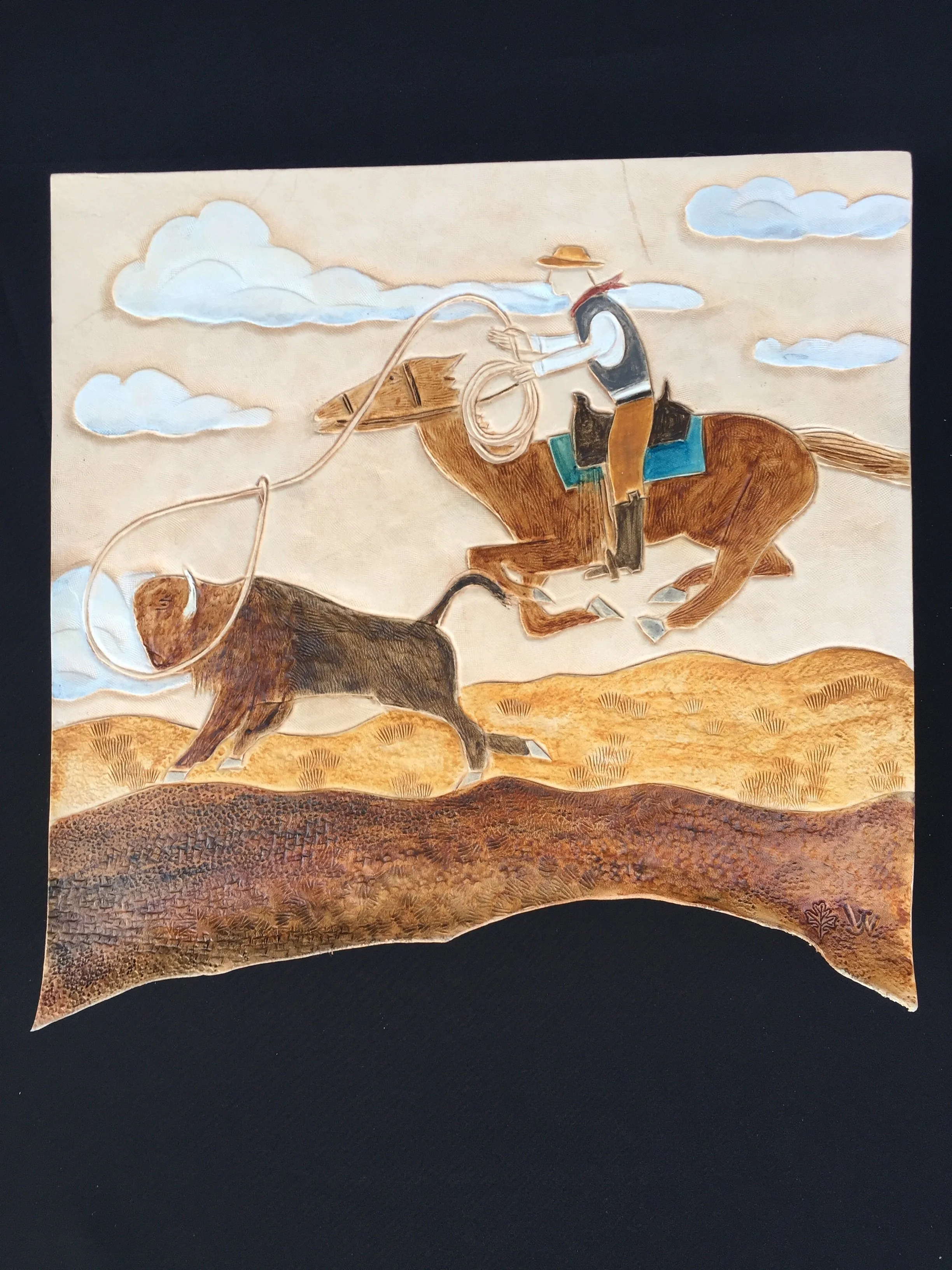

Swore He was Going to Rope a Big Buffalo Bull

11 ¾” x 12” Acrylic on tooled leather

“This was the first time that I, and several of the other cowboys, had ever seen buffalo, and we were all greatly interested in them.”

“One of the boys, a strapping Castroville youth, swore he was going to rope a big buffalo bull. The old hands urged him not to risk it, but he stuck to his plan, despite the fact that he rode a small horse that did not weigh over eight hundred pounds.

His opportunity came a few days later when a bunch of big buffalo bulls ran though the herd and one of the animals ran by this chap. He sent his lasso flying and caught the big shaggy around the neck, but the powerful bull rushed on, jerking horse and rider, like toys to the ground. Luckily the Castroville cow-puncher was uninjured and quickly cut the rope with his knife. That was the last I heard on the trip about roping a buffalo bull”. (1873)

Frank Collinson, Life in the Saddle

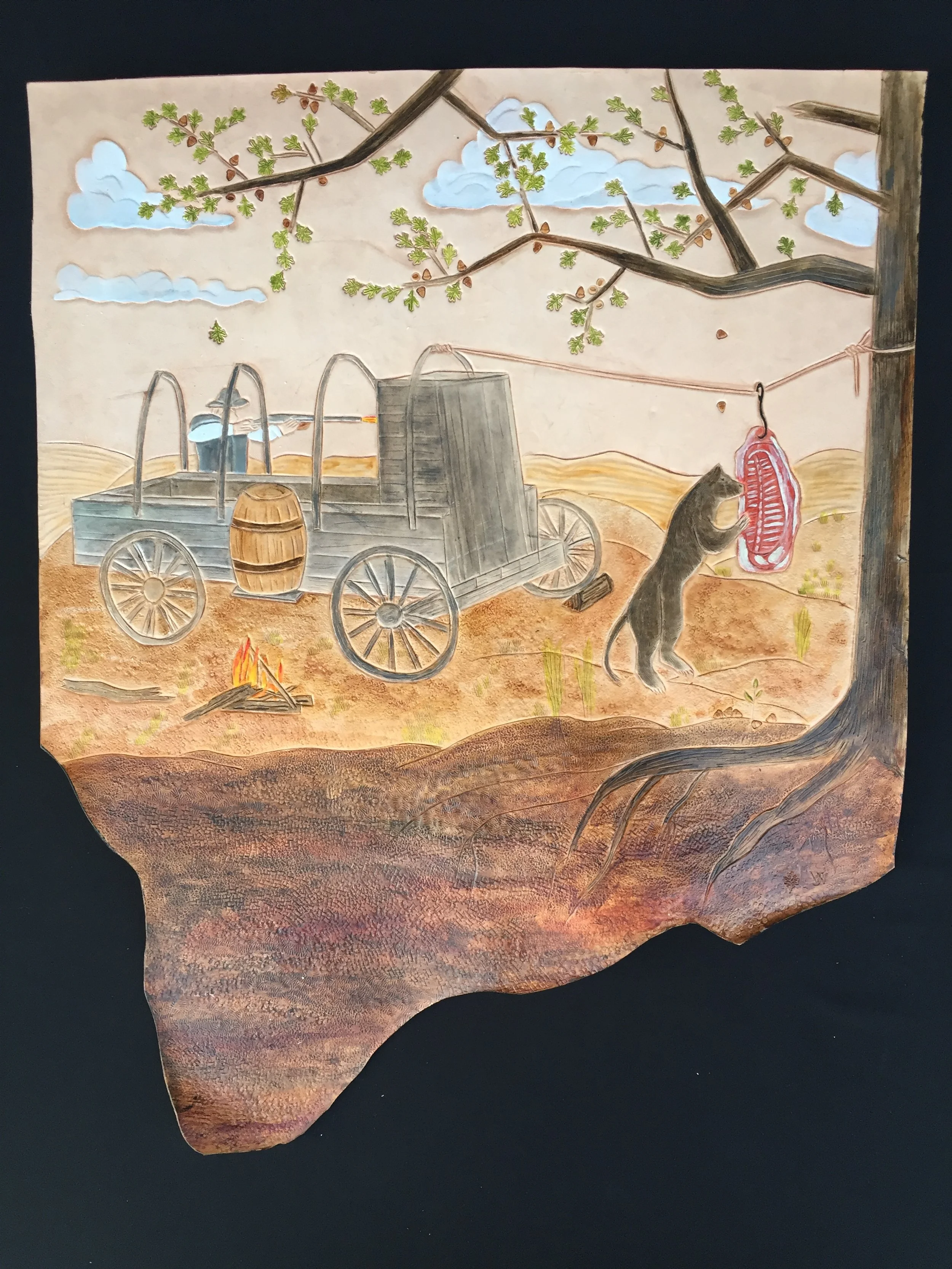

He Discovered a Panther

28” x 22” Acrylic on tooled leather

“When we arrived at old Red River Station, where the old Chisholm Trail crossed, we found the river up and several herds waiting to cross. We killed a fat yearling—I won’t say whose it was—tied a rope to one end of the front bow of the wagon, the other to a small tree; the cook hung the beef on the rope.

When the boys came in a 12 o’clock to wake up the third guard he discovered a panther standing on his hind feet eating the meat off of the rope, just on the opposite side of the wagon from where we were sleeping.

He opened fire with is forty-five on the panther. We thought “horse rustlers”, now commonly called horse thieves, had attacked the camp. The noise of the firing stampeded the cattle. As the boys sprang out of their blankets some had their forty-fives ready and some made for the horses, where it took but a moment to saddle and then off for the cattle.”

G.W. Mills, Trail Drivers of Texas, pg 231.

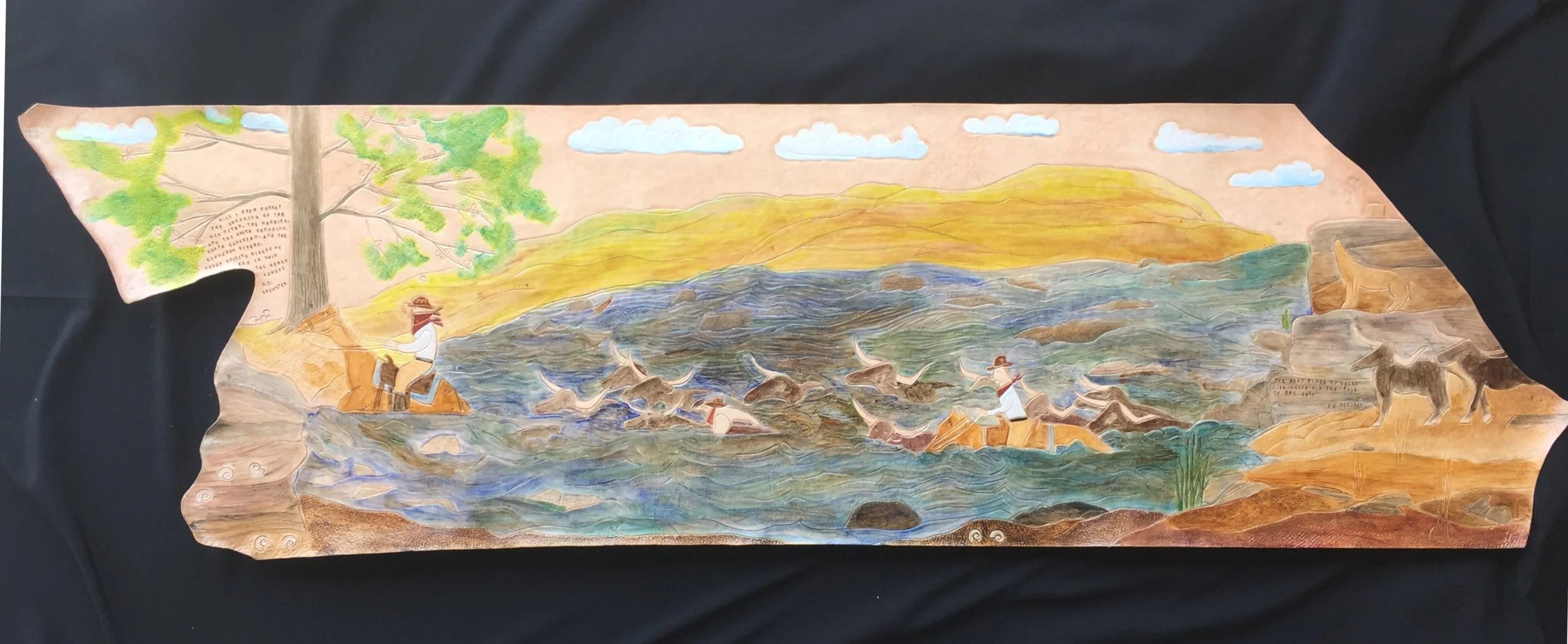

Will I Ever Forget

54” x 18”, Acrylic on tooled leather

River Crossings were a major hazard to the cattle drive. Inducing the cattle to cross, quicksand, rough water, and the possibility of drowning all contributed to the difficulty.

“Will I ever forget the crossing of the Red River, the Washita, and the South Canadian, the North Canadian, and the Cimarron Rivers, those muddy boiling rivers we had to swim the herds across.” (O. E. Brewster in Trail Drivers of Texas).

“We did not realize fully the treachery of this river until we saw that twenty cattle were caught in the merciless grasp of the quicksand.” (Andy Adams, The Log of a Cowboy).

“…bunch of his cattle milled in the swollen Red River. One of his men rode his horse out into the circling longhorns, mounted the biggest steer, and headed for the north bank.” (Col. W.M. Todd quoted in Gard, The Chisholm Trail).

“Some few never came back, but were buried along the lonely trail, among the wild roses, wrapped only in their bed blankets. No human being living near, just the coyote roaming there.” (W.F. Cude in the Trail Drivers of Texas).

“The best place to learn cuss words is the tail of the herd”. (J. L McCaleb quoted in Gard, The Chisholm Trail).

The Acanthus Rose

21” x 5 ½”, Acrylic on tooled leather

An old style of leather-tooling uses acanthus leaves and cliff roses. These became popular in the singing cowboy era of the 1930s, and floral designs still dominate western leatherwork. In my interpretation the flowers become wild and colored, the acanthus leaves unfurl, and all are reconnected to their roots.

“Some few never came back, but were buried along the lonely trail, among the wild roses, wrapped only in their bed blankets. No human being living near, just the coyote roaming there.” (W.F. Cude in The Trail Drivers of Texas).

In the Indian Territory

16” x 11 ½” Acrylic on tooled leather

Scissortails and blanket flowers became predominant once the Red River was crossed and the drives entered the Indian Territory.

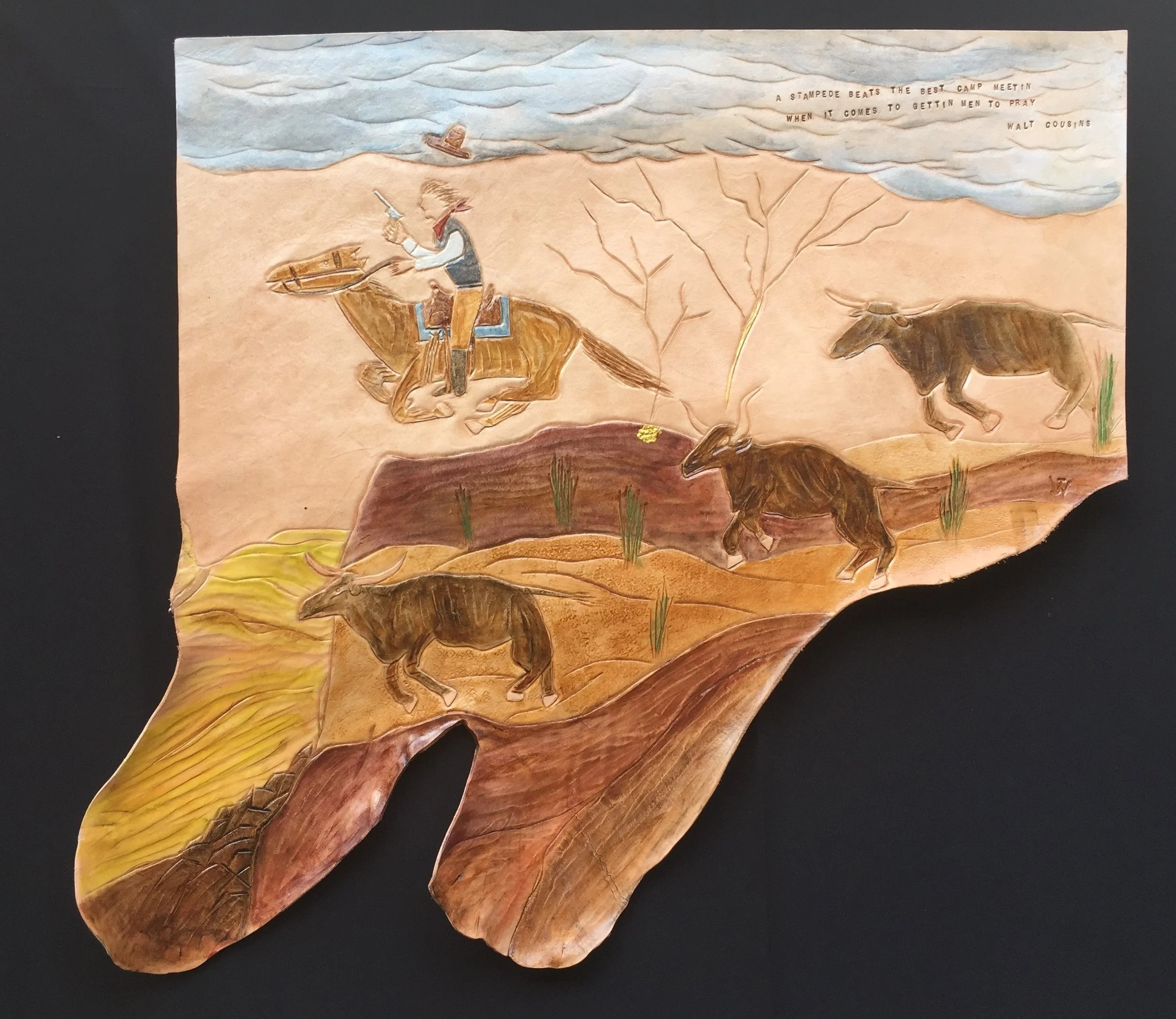

The Best Camp Meetin’

20 ½” x 21”, Acrylic on tooled leather

Stampedes were one of the most dreaded aspects of cattle drives. A wild ride to stop the stampede, high potential for injury, hours and hours to quiet the cattle, and much work to find and sort out mixed herds formed the hardships of stampedes.

“A stampede beats the best camp meetin’ when it comes to gettin’ men to pray.” (Walt Cousins, The Stampede quoted in J. Frank Dobie, The Longhorns).

The Best Camp Meetin’ references four stories:

“The punchers with their six-guns, shot at one side of the leaders to try to turn the herd into a mill. This time they didn’t succeed. The maddened brutes rushed over the bank of a ravine.” (Gard, The Chisholm Trail).

“My companion and his horse seemed poised in mid-air for a moment, far over the edge of a high bank of the creek.” (J. H. Cook quoted in Gard, The Chisholm Trail).

“My horse stopped dead in his tracks, almost throwing me over the saddle horn. The lightning showed that he was planted hardly a foot from the edge of a steep-cliffed chasm.” (R. Hill, quoted in Gard, The Chisholm Trail).

“During a storm in 1882, while I was delivering cattle to Gus Johnson, he was killed by lightning. G. B. Withers, Johnson and I were riding together when the lightning struck. It set Johnson’s undershirt on fire and his gold shirt stud, which was set with a diamond was melted and the diamond was never found. His hat was torn to pieces and mine had all the plush burned off of the top. I was not seriously hurt, but G.B. Withers lost one eye, by the same stroke that killed Johnson.” (M.A. Withers in The Trail Drivers of Texas).

Estampedia/Stompede

30” x 11”, Acrylic on tooled leather

The dreaded stampedes could be caused by almost anything. Common causes were the howl of the coyotes, lightning, breaking of a stick, striking of a match, sneeze of a cowboy, etc.

“…full moon rising between the two peaks of a cleft hill and shining red and large over a little valley that had been quite dark until then, once caused one of the most uncontrollable of stampedes.” (Emerson Hough, The Story of the Cowboy, 1927).

Cattle Fever

19 ½” x 19 ½”, Acrylic on tooled leather

Domestic cattle sickened and died when brought in contact with longhorns. The cause of the cattle fever wasn’t found until 1890. Meanwhile, Kansas and other states passed quarantine laws that pushed the cattle drives progressively to the west. Ticks which carry a parasite still infect cattle and are treated with a pesticide to control outbreaks.

Ultimately, the quarantines, fencing of the prairies, and the advent of refrigerated rail cars brought an end to the cattle drive era.

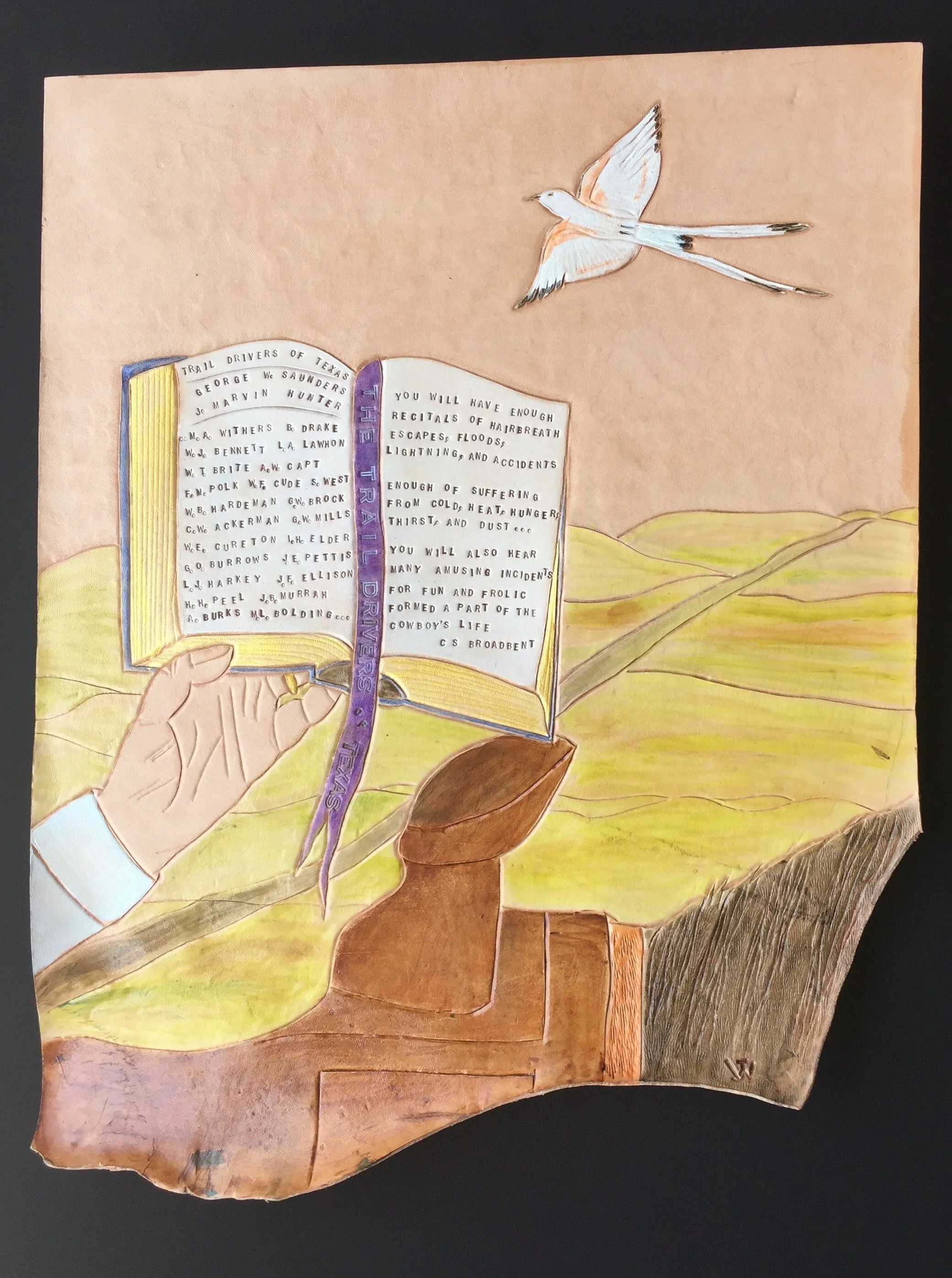

The Trail Drivers of Texas

20” x 16”, Acrylic on tooled leather

The Trail Drivers of Texas was published in 1920 and presents about 150 first-hand recollections of trail drives. It has been used as a source by every author of books on the cattle drives. The stories were written and collected at the urging of George W. Saunders and compiled by J. Marvin Hunter. Although written 40 and 50 years after the fact, and tinged with nostalgia, the reminiscences provide an invaluable source on the cattle drives and were instrumental in producing this project.

“On my way home I reviewed my past life as a cowboy from every angle and came to the conclusion that all I had gained was experience and I could not turn that into cash. So I decided I had enough of this and made up my mind to go home, get married and settle down to farming.” (F. M. Polk in The Trail Drivers of Texas)

“None of my boys have ever been sent to the penitentiary or elected to the legislature, and I think that’s a pretty good showing. (W.T. Brite in The Trail Drivers of Texas).

“Those old days may have been a little rough at times, but there always was such kindness and good feeling among the boys, it’s a pleasure worth remembering to have been one of them.” (H.H Peel in The Trail Drivers of Texas).

“I met many brave and fearless men during those times. They were rough outside but refined in heart and soul… We would pitch our tents at night, get all our work done and after supper would light our pipes and site or lounge around the campfire and listen to the other men spin their hair raising yarns of earlier trips…Arrived at Austin…feeling like I had seen the world, and with much pride telling the boys all that I had seen and been through.” (G. W. Mills in The Trail Drivers of Texas).

Wound up in 1882

16 ½” x 10 “, Acrylic on tooled leather

The cowboys wrote of their varying experiences—a mix of the positive and the negative.

“Wound up in 1882 without a dollar in hand, but in possession of several thousand dollars worth of fun.” (Gus Black in The Trail Drivers of Texas).

“Some of my experiences were going hungry, getting wet and cold, riding sore-backed horses, going to sleep on herd and losing cattle, getting ‘cussed’ by the boss, scouting for ‘gray backs’ trying the ‘sick racket’ now and again to get a night’s sleep, and other things too numerous to mention, but all of this was forgotten when we delivered our herd and started back to Texas.” (G. O. Burrrows in The Trail Drivers of Texas).

“So sick and lonely, was such a fool to come on this trip.” (J. Bailey, A Texas Cowboy’s Journal: Up the Trail to Kansas in 1868).

“When I recall that the first long cattle drive to the Northwest and think of the hardships we experienced, I wonder if there was really such glamour or adventure to the trip. It was 98 percent hard work, but I am glad I had the experience…” (Frank Collinson, Life in the Saddle).

A Sunflower of Kansas

15 ½” x 7”, Acrylic on tooled leather

Many trail drives started in early April, and drovers reported on the beauty of the landscape.